Is there a “skill at thinking” separate from IQ?

The current science of forecasting generalizability, with a whirlwind tour of Philip Tetlock’s career.

As a reader of Sportspredict-stack, you’re probably pretty good at predicting things like which team will win a baseball game or who’s set to be awarded the Ballon D’Or.

What does this say about you?

One of the central claims behind Philip Tetlock-ism—and SportsPredict, for that matter—is that the answer is: quite a bit. It signals not only that you have domain expertise, but that you’re endowed with a sturdy set of epistemic habits—call them forecasting g, like the g factor of correlations across intelligence tests—that are also useful when asking “Will Russia invade Ukraine?”, “Which test could disconfirm your hypothesis?” or “What stocks should I buy?”

This article examines the evidence for that claim, and the fellow who did the most to gather it: Phil Tetlock.

The vindication crisis: Tetlock and Ioannidis

If we’re searching for forecasting g, Philip Tetlock’s work is the obvious first place to look. If Hanson is the Darwin of forecasting, then Tetlock is its Galton: his distinctive contribution was to operationalize groundbreaking but abstract theory in the domain of social science by running the important experiments, writing popular books, and building the institutions of the field. Though Tetlock remains an underrated American1 intellectual among the general public, he’s long been the subject of encomium within his field.

The origins of Tetlock’s forecasting research go back to the early 1980s, when he was a professor at UC Berkeley, newly tenured at the exceptionally young age of 30. In 1983, he began his long relationship with the intelligence community, serving on a government panel charged with forecasting Soviet behavior. He recounted the experience in his 2016 book Superforecasting.

The panel included, he wrote, “three Nobel laureates… the economist Kenneth Arrow, and the unclassifiable Herbert Simon—and an array of other luminaries, including the mathematical psychologist Amos Tversky.” But there was trouble in social science paradise: The panel was dominated, in practice, by now-forgotten professional Sovietologists whose confidence dwarfed their accuracy.

Soviet history during Ronald Reagan’s second term was unusually eventful: Andropov’s brief ascent, boring Chernenko’s impending death, and his sudden replacement by the seismic Mikhail Gorbachev. (“How am I supposed to get anywhere with the Russians,” Reagan quipped, “if they keep dying on me?”) But this glut of new information rarely changed minds. Instead, it was merely absorbed as confirmation of whatever pundits already believed. The right-leaning experts saw each new story of the day as proof of the threat the USSR posed to America and Reagan’s strategic brilliance; left-leaning experts interpreted the same facts as evidence of hawkish overreach and the sclerosis of Cold War thinking. It was this encounter with the dysfunctional culture of Cold War punditry—confident, ideological, and unaccountable—that negatively polarized Tetlock against expert judgment. And as with Stanley Kubrick, this attitude was to inspire Tetlock’s most influential work.

…Or at least that’s how he often presents it to normies. For more inframarginal consumers of social science like you, dear reader, I think it’s safe to say that the then-cutting-edge research of Kahneman and Tversky was also on Tetlock’s mind; he hints at this. For decades, there was evidence that people perform inexplicably badly with predictive decision-making. Kahneman and Tversky—the legendary progenitors of much of modern academic social science—collected all this and integrated it in an ambitious new model of human decision-making. Tetlock’s project was essentially an extension of this tradition: Do experts make the same systematic errors?

It was 1984 that Tetlock began Expert Political Judgment: convincing hundreds of political and economic pundits to provide regular probabilistic forecasts of world events, and tracking those forecasts for decades. Between 1984 and 2004, he collected some 30,000 forecasts from about 300 experts.

Unsurprisingly, this took a while to pay off—which is likely a major reason no one had done it before2—but we live in a world where it did.

By the early 2000s, enough of their forecasts had resolved to score pundits’ performance. The verdict was decisive—and, for experts, disastrous. The average expert didn’t outperform random guessing, and performed significantly worse than simple statistical heuristics such as “extrapolate the current trend” or “assume no change.” They failed even to measurably outperform educated laymen.3

This was, and remains, a very powerful critique. Quoth Hanania’s magisterial 2021 essay “Tetlock and the Taliban”:

Phil Tetlock’s work on experts is one of those things that gets a lot of attention, but still manages to be underrated. In his 2005 Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, he found that the forecasting abilities of subject-matter experts were no better than educated laymen when it came to predicting geopolitical events and economic outcomes. As Bryan Caplan points out, we shouldn’t exaggerate the results here and provide too much fodder for populists; the questions asked were chosen for their difficulty, and the experts were being compared to laymen who nonetheless had met some threshold of education and competence.

At the same time, we shouldn’t put too little emphasis on the results either. They show that “expertise” as we understand it is largely fake. Should you listen to epidemiologists or economists when it comes to COVID-19? Conventional wisdom says “trust the experts.” The lesson of Tetlock (and the Afghanistan War), is that while you certainly shouldn’t be getting all your information from your uncle’s Facebook Wall, there is no reason to start with a strong prior that people with medical degrees know more than any intelligent person who honestly looks at the available data.

In August 2005, around a month after Philip Tetlock published Expert Political Judgment, John Ioannidis published “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False,” kicking off what we would later come to call the replication crisis. In retrospect, Tetlock’s project was always a close cousin. Just as the replication crisis revealed that enormous swaths, even whole subdisciplines of modern science aren’t demonstrably real, Tetlock revealed that most experts’ pretensions to special understanding of the world do not survive basic scorekeeping.

The narratives have the same moral: In the modern West, prestige has been a decidedly overrated proxy for epistemic competence.4 Like Ioannidis, Tetlock used the tools of social science to find the limits of social science.5

Yet Tetlock’s critique was not nihilistic. Fortunately for epistemology in general, hidden in the rubble of expertise was the suggestion of something more robust. If Tetlock found most experts incompetent, some still reliably outperformed others. And perhaps as famous as his finding that expertise was fake was Tetlock’s discovery that these better forecasters shared some non-obvious intellectual habits.

Superforecasters and proto–forecasting g

One person who wrote on Tetlock’s findings very eloquently was Hal Finney, of inventing Bitcoin fame.6 Quoth his 2006 article in Robin Hanson’s Blog:

[Tetlock’s] first effort was to look for factors that correlate with prediction accuracy. He focused on three categories: differences in background and accomplishments; different [sic] in content of belief systems; and differences in styles of reasoning.

The first category produced no statistically significant correlations. Factors such as education, years of experience, academic vs non-academic work, and access to classified information were not significant.7 The strongest effect here was a mild negative correlation to fame: the better known an expert was, the poorer he did.8

Among factors relating to belief content, left-right ideology and idealist-realist distinctions were not significant. There was a weak statistically significant measure Tetlock calls doomster-boomster relating to optimism about human potential. Generally for all these categories the moderates did somewhat better than the extremists.

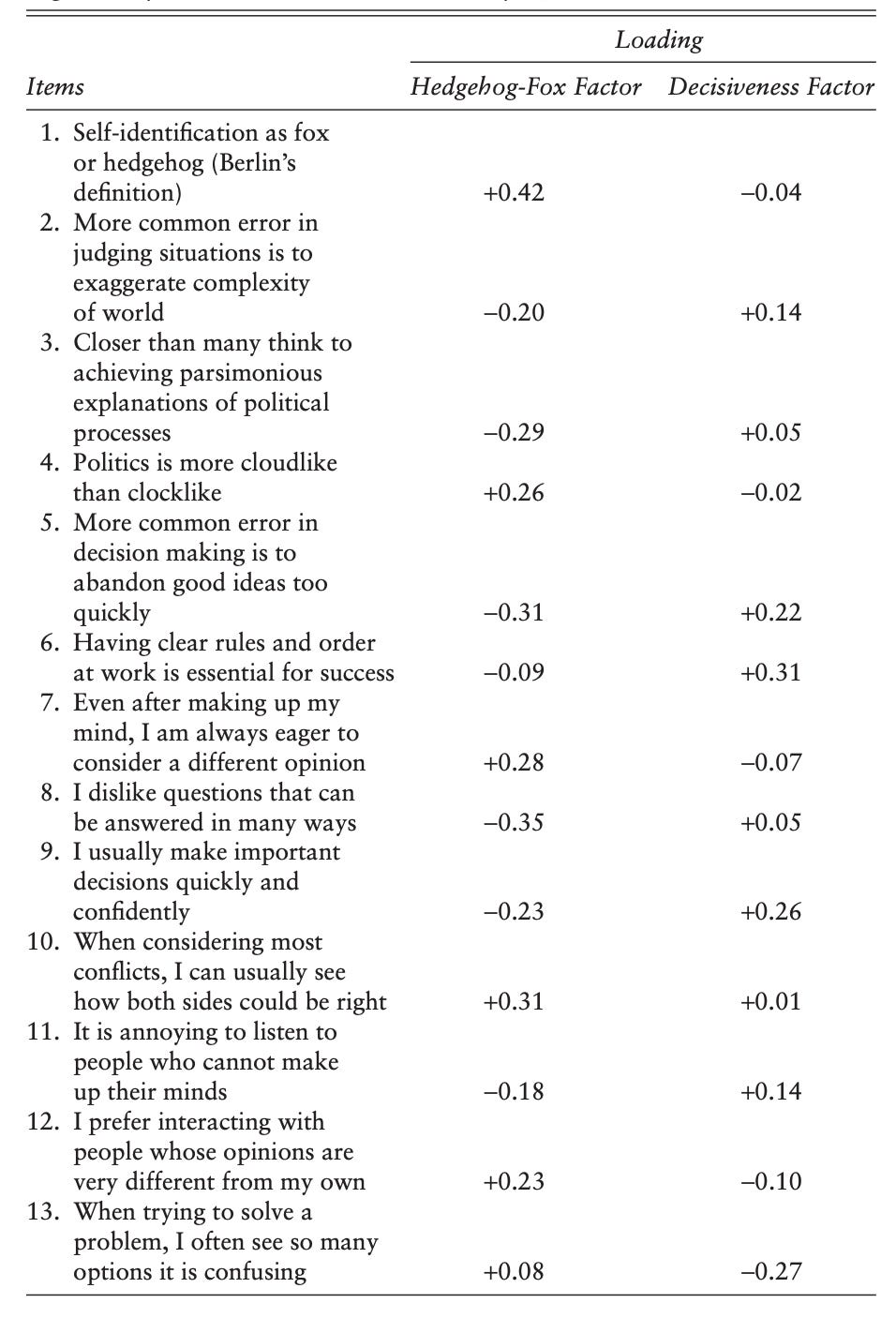

Where educational and professional background and belief content failed to predict accuracy(!), Tetlock also tried subjecting his Expert Political Judgment test subjects to a Styles‑of‑Reasoning Questionnaire that tried to capture how they thought—as well as an integrative complexity index based on their written forecast rationales that intellectual history doesn’t remember as well.9

This Styles‑of‑Reasoning Questionnaire was Tetlock’s bespoke creation, operationalizing a well-loved concept from the social theorist Isaiah Berlin (perhaps the world of ideas’s most accomplished Latvian): the dichotomy between “hedgehogs” and “foxes.” Hedgehogs are intellectuals who see the world through one big, unifying idea—“everything is really about class struggle,” “everything is really about institutions,” or “everything is really about the Jews.”10 Foxes, by contrast, are intellectual omnivores: they take bits of insight from across disciplinary boundaries, and are happy to weigh multiple models at once.

Tetlock built the questionnaire out of thirteen items: eight borrowed directly from social psychologist Arie Kruglanski’s older Need for Cognitive Closure measure, plus five Tetlock wrote himself to directly bring in Berlin. If you’d like to play yourself, here’s the text of one question:

Isaiah Berlin classified intellectuals as hedgehogs or foxes. The hedgehog knows one big thing and tries to explain as much as possible within that conceptual framework, whereas the fox knows many small things and is content to improvise explanations on a case-by-case basis. I place myself toward the hedgehog or fox end of this scale.

After running factor analysis on all thirteen items, one strong factor stood out: having little need for closure, high comfort with ambiguity, and placing oneself as a “fox.” In layman’s terms: responses to the survey items covaried consistently across respondents. This persuasively suggested the influence not of a patchwork of unrelated inclinations that affect forecasting in different ways, but of a more fundamental trait beneath the surface11 that Tetlock would call cognitive style. And thus—fully formed like Athena from Zeus's head—the hedgehog–fox cognitive-style scale was born. Quoth Finney again:

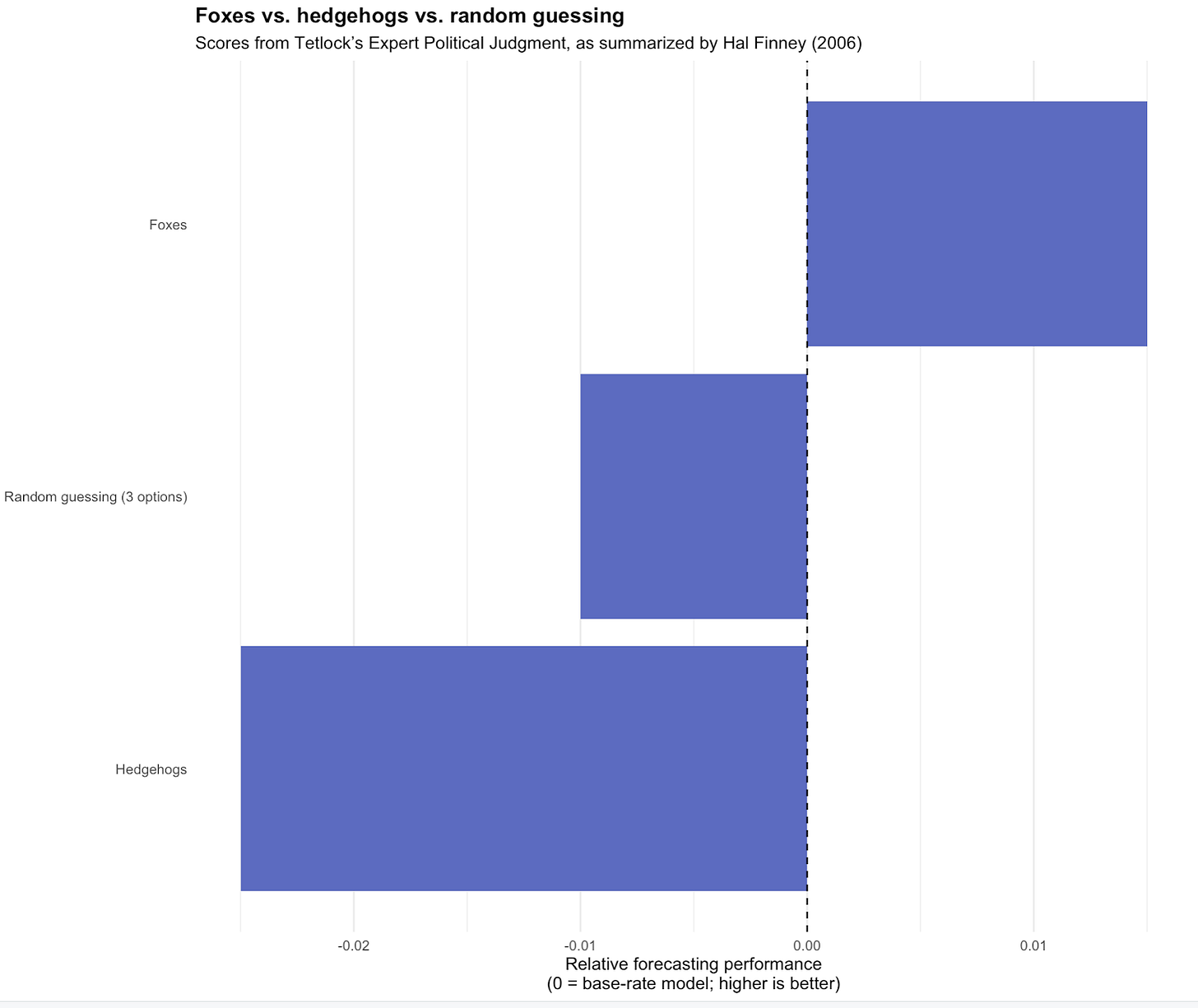

It was in cognitive style that the strongest correlation was found, statistically significant at the 1% level. And that is the Fox-Hedgehog distinction. Let’s re-do the table above [showing the success of various prediction methods, for which higher is better] and put in Foxes and Hedgehogs:

-.045 – Expansive base rate model (recent past)

-.025 – Restrictive base rate model (recent past)

-.025 – “Hedgehogs”

-.01 – Chimps [random guessing]12

0.00 – Contemporary base rate model

0.015 – “Foxes”

0.025 – Aggressive case-specific extrapolation model

0.035 – Cautious case-specific extrapolation model

0.07 – Autoregressive distributed lag models

It’s worth stopping for a second and appreciating how impressive Tetlock’s achievement is in modern intellectual history. In psychology, a small number of constructs—intelligence, conscientiousness, neuroticism—tend to do literally all of the work in predicting outcomes. Decades of attempts to uncover new measurable cognitive traits that reliably predict outcomes (generally as levers to push on) have produced results nigh as underwhelming as the political judgment of Tetlock’s experts.

Tetlock did find such a thing: Across the literature, Fox-Hedgehog cognitive style tends to do about as well as IQ at predicting forecasting performance—and in the most important dataset, Tetlock’s Good Judgment Project, it squarely outpoints the Ravens’ Progressive Matrices (−0.23 vs −0.18). And this “foxy”/open-minded disposition isn’t just IQ in disguise—as is so often the case in the social science of constructs. “Fox-like” cognitive style correlates with cognitive ability, but not so strongly that it collapses into it—establishing what in social science is called “discriminant validity.”

What a fascinating modern case of the less empirical humanities contributing to developments in social science!

Good judgment outside forecasting

But is cognitive style forecasting g?

Well, it’s certainly close: Fox-like cognitive style is important for forecasting in a way that ungeneralizable domain expertise isn’t. Still, as promising as theory is to determine the validity of the hypothesis that forecasting ability generalizes between domains, it is, at the end of the day, an empirical question.

I looked around, and the best paper looking into this is 2017’s “How generalizable is good judgment?” This article is about the social science of forecast generalizability and not just Philip Tetlock’s biography so I’ll write a description of it even though Tetlock wasn’t the primary author of this one. Because in this case it was his wife, fellow Penn psychology professor Barbara Mellers.13 And Tetlock was a coauthor.14

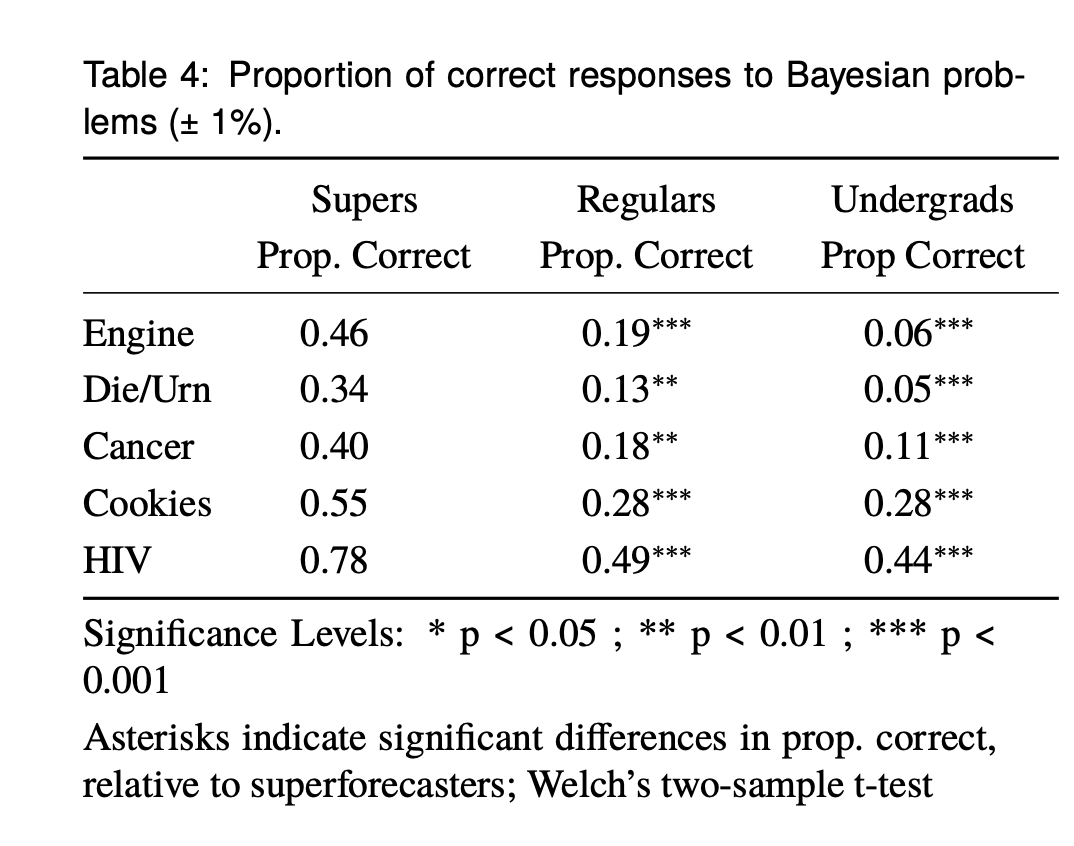

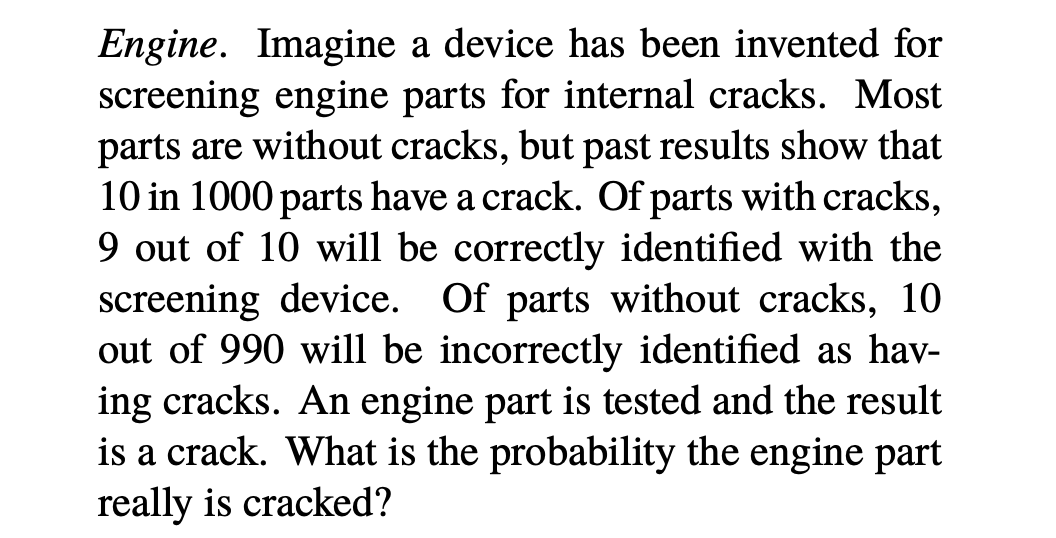

Mellers et al. administered a standard battery of cognitive-psychology tasks to three groups—Good Judgment Program superforecasters, regular forecasters, and undergrads.

The superforecasters did far better than their less exceptional counterparts, on every one of the tests surveyed: If you squint and average across the tasks, superforecasters are roughly 15–20 percentage points more likely than regular forecasters to give the normatively correct answer, and on the hardest Bayesian items often about twice as likely.

Then they built a composite “good judgment” score, incorporating coherence, consistency, and discrimination, and investigated how tightly it mapped onto whether someone was a superforecaster. The correlation comes out around r ≈ 0.46 in one survey and r ≈ 0.60 in another; after correcting for measurement error, those jump to roughly r ≈ 0.73–0.82.

That’s a real effect; the kind of number that makes one comfortable using the term “factor” without blushing. Though it’s important to note that no paper is that good, there is certainly the suggestion of a general skill of probabilistic reasoning and epistemic hygiene that shows up across different tasks, not only in the very specific situation of forecasting.

In layman’s terms: The superforecaster advantage looks to be a genuine, important general factor!

The Good Judgment Project and Forecaster Training

But is this trainable?

Fast-forward a couple of decades later in Tetlock’s career. In the late 2000s, forecasting had become significantly more salient in the wake of 9/11 and the failure to find WMDs in Iraq. As the most eminent scholar in forecasting, Tetlock was well-positioned to reap the rewards.

IARPA, the Intelligence Community’s then-new DARPA‑like15 research shop, funded several teams to run a multi‑year geopolitical forecasting tournament: the Aggregative Contingent Estimation. By the second season, Tetlock and Mellers’s team—the Good Judgment Project—had a lead so large that (per Good Judgment’s own write‑up) IARPA ended the head‑to‑head competition early and continued funding Good Judgment for the final years of the program.

Thousands of volunteers made over a million forecasts on ~500 questions about politics, economics, security, public health, and so on—creating the most important dataset available to assess the social science questions raised by forecasting.

“Hedgehogs and foxes” continued to hold up in the Good Judgment Project data. But also interesting for our purposes was that training turned out to matter modestly in absolute terms but hugely relative to how little was required.

Forecasters were randomly assigned to get (or not get) a short online module—on the order of an hour—covering the basics of probabilistic reasoning. In Scott Alexander’s summary, drawing on Tetlock’s own numbers, that one-hour training produced roughly a 10% improvement in Brier accuracy (the standard mean‑squared‑error metric for probability forecasts) versus no training.

That’s very much not nothing. In a domain like psychology where most interventions have basically zero effect, a “webinar” that shifts accuracy by ≈10% is strong evidence that forecasting skill is, at least in part, trainable.

Sports and Reason?

It’s established that forecasting skill is real and correlates with one’s ability to do other probabilistic tasks, has a lot to do with cognitive style, and is somewhat trainable. Still, this is an area rich in possible research questions.

When a student is trained in forecasting, for instance, is the old “fox and hedgehog” dichotomy the lever that’s pushed on? And could we find an intervention that’s more effective? The 10% gain from Good Judgment Project’s one-hour module isn’t, in the end, groundbreaking.

How coherent is forecasting g factor-analytically? The “How Generalizable Is Good Judgment?” paper provides a composite “good judgment” factor that correlates ~0.5–0.6 with superforecaster status. That’s indeed quite strong. But what’s the internal structure of that factor? Is it “IQ + actively open-minded thinking,” or are there separable sub-factors (calibration? scope sensitivity? bias detection?) that could be trained or selected for differently?

What is the relationship between forecasting g and what we call “wisdom”?

And, finally, one thing we don’t have—yet—is a paper that says:

“We took this cohort, measured their performance on forecasting world events and on forecasting sports, and the correlation in accuracy was r = 0.7”

The main forecasting datasets are rich in geopolitics and macroeconomics, but poor in sports, law, and the interpersonal. There are sports datasets, too, but though great on prices and money, they’re poor on individual track records across domains.

SportsPredict exists—in very small part—to create the dataset I wish already existed. Until then, the working hypothesis is clear:

If you’re good at forecasting Arsenal vs. Spurs for reasons that survive contact with the Brier score, you’re probably good at forecasting more than just football. And we’d like to help you prove it.

Canadian-American, to be precise.

Bryan Caplan has persuasively argued that while the standard idealist defense of tenure is that it enables scholars to pursue intellectually risky projects with back-loaded returns, in practice, its effect is usually the opposite. Tenured faculty frequently phone in the remainder of their careers, with job security functioning as non-wage compensation rather than as risk capital for bold work. But—as happens an underrated amount—Tetlock plays the gadfly to Caplan’s worldview. In Expert Political Judgment, Tetlock writes in the acknowledgments:

“The project dates back to the year I gained tenure and lost my generic excuse for postponing projects that I knew were worth doing… but also knew would take a long time to come to fruition.”

As Caplan wrote in his review of Expert Political Judgment:

“Tetlock made a decision that should thrill defenders of the tenure system.”

How this fits into the still relevant debate between Kahneman’s Prospect Theory and the Ecological Rationality paradigm associated with Gerd Gigerenzer is pretty interesting: The fact that simple heuristics—base-rates or “predict no-change”—often match or outperform expert judgment in Expert Political Judgment vindicates the core Gigerenzerian intuition that fast, frugal strategies can dominate more elaborate reasoning in the right environments. Tetlock touches on this here.

It’s unsurprising then that they to some extent shared an audience: The well-informed bit of the political right.

Maybe some bold soul would add Hayek to the list as well.

And this wasn’t even a celebrity guest post! The Café Central-like quality of the early rationalist blogosphere is often underestimated. Said Hanson in 2014:

Hal Finney made 33 posts here on Overcoming Bias from ’06 to ’08. I’d known Hal long before that, starting on the Extropians mailing list in the early ‘90s, where Hal was one of the sharpest contributors. We’ve met in person, and Hal has given me thoughtful comments on some of my papers (including on this, this, & this). So I was surprised to learn from this article (key quotes below) that Hal is a plausible candidate for being (or being part of) the secretive Bitcoin founder, “Satoshi Nakamoto”.

Fit that into your worldview!

And that too!

Though it is remembered pretty well within its domain. Tetlock and Peter Suedfeld had spent years developing a human-rated measure of how differentiated and how well-integrated a person’s reasoning is—using it to analyze foreign-policy speeches as far back as the late 1970s and 80s, while Tetlock was at Berkeley. Those efforts culminated in the Suedfeld–Tetlock–Streufert (1992) coding manual, which laid out the 1–7 scale and decision rules that Expert Political Judgment came to rely on for its “coder-rated integrative complexity” scores. The Suedfeld–Tetlock–Streufert coding manual remains the standard reference for assessing conceptual complexity in communicative data.

With modern LLMs to take up the once labor-intensive task of assigning integrative complexity scores to text, could we be primed to see a lot more use of the Suedfeld–Tetlock manual in social science? I’ll leave that an exercise for the reader (or perhaps even the writer).

Or—dare I say—“everything is really about the Lindy Effect,” “everything is really about engineers vs lawyers,” and “everything is really about POWER.”

I.e. not directly observable like height, but inferable from patterns of behavior, much like intelligence.

The use of the metaphor of a blindfolded monkey throwing darts to denote a random walk originates in Burton Malkiel’s famous work of that name. Still, the now common “chimp” phrasing was arguably popularized by Tetlock.

By combined h-index they must be one of the leading couples in the world of ideas—plausibly in the top-10 most-cited married pairs in American social science. And tastefully h-index matched.

The fact that you can write an article about modern literature in social science and make it about him is a reflection of his titanic dominance of this subdiscipline. The Gretsky of decision science.

In the early 2000s DARPA actually had a “crowd/market forecast national-security questions”-project of its own—which counted among its leaders none other than Robin Hanson. FutureMAP, whose most famous sub-project was the Policy Analysis Market—a public-facing prediction-market pilot on geopolitical instability—was abruptly cancelled in 2003 amid accusations that PAM was funding markets on terrorist attacks (which wasn’t, in a strict sense, true). Presumably, some of the lessons of this experience informed the design choices of the Aggregative Contingent Estimation.

As someone in the approximate "superforecaster" range there's a big gap between my subjective experience of forecasting and what the generalizability literature seems to say. There's a big emphasis on cognitive and personality factors. But when I try to improve my own forecasting performance, achieving a Zen-like state of contemplation has really nothing to do with it. I am gathering information and trying to better understand the specific domain and the specific question I'm forecasting on. Domain knowledge seems like by far the highest-leverage factor. This leads to a puzzle because formal domain expertise doesn't seem to predict forecasting success basically at all.

I can think of several ways to resolve the puzzle:

* Domain experts don't really have domain expertise. "Experts" means mostly academics, whose real expertise is in abstruse theoretical frameworks with limited applicability to the real world. Their domain-level expertise is gotten informally "on the job" and is in principle readily available to anyone; they are frequently outdone on this by randos.

* Domain experts have legitimate domain expertise but they're sufficiently good about disseminating it that a non-expert can quickly gain most of the predictive benefit of expertise by skimming the expert literature and looking at secondary sources who have themselves done so. Basically, domain experts are searching depth-first so as to mine PhDs and citations, whereas non-experts trying to make practical forecasts need a breadth-first view at which PhD experts don't greatly outperform them.

* Domain experts have legitimate domain expertise that is *not* readily accessible to nonexperts such as forecasters, but few domain experts *also* have the cognitive and personality traits to be expert forecasters, without which their expertise is useless for forecasting purposes and does not show up in the data. Domain experts also face poor professional incentives for accurate forecasts, such as returns to overconfidence, safety-in-herding behavior, etc. In principle, expert forecasters who also became legitimate domain experts would do even better at forecasting.

* Domain experts have legitimate domain expertise, *and* this expertise is not easily sharable to nonexperts such as generalist forecasters, *and* many domain experts make legitimately good expert forecasters, *but* those people are so valuable that they take their abilities private and never develop the formal domain credentials to show up in research as "domain experts" to the true extent of their expertise. Neither credentialed experts nor "smart generalists" actually outperform these people, they're just not *the same* people who show up in Tetlock-style surveys of "experts".

In practice it probably has to be most or all of these factors working together in combination, yeah?

Need for cognition is probably the skill for thinking